ĐƯỜNG

MÒN HCM

Giới thiệu chuyến đi của tác giả

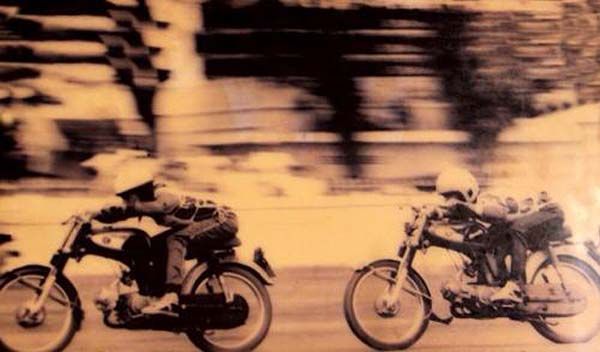

Được xây dựng, xử dụng trong thời gian 1959 – 1975,

đường mòn HCM trải dài 12000 (ngàn) dặm xuyên qua những cánh rừng núi Việt Nam,

Lào và Cambodia. Được xem như một công trình vĩ đại nhất của Công Binh (quân đội)

trong lịch sử, con đường là kết hợp giữa trí sáng tạo và sự quyết tâm bằng máu,

phương tiện để Bắc Việt nuôi dưỡng, chiến đấu trận chiến chống lại Miền Nam được

người Hoa Kỳ yểm trợ. Không có đường mòn HCM, có thể sẽ không có chiến tranh,

thực ra người Hoa Kỳ biết rất rõ về con đường. Trong tám năm ròng rã tìm cách

phá hoại, Hoa Kỳ đã thực hiện 580,000 phi vụ, thả hơn 2 triệu tấn bom xuống một

phần đường mòn HCM nằm trên quốc gia trung lập Lào, ngoài ra còn thả thuốc khai

quang phá rừng. Đã có lần Tổng Thống Nixon có ý định xử dụng vũ khí nguyên tử.

Trong khi có nhiều du khách đi du lịch trên những nhánh

của hệ thống đường mòn HCM giữa Saigon và Hà Nội, chỉ có một số rất ít dám băng

qua dẫy Trường Sơn qua nước Lào. Càng ít hơn khi đi trên con đường về hướng đông

sang đất Cambodia. Cô Antonia muốn thực hiện cả hai chuyến. Không như hàng trăm

ngàn người miền Bắc lội bộ, đi xe hoặc làm việc trên con đường trong hai thập

niên 60, 70, cô ta không lo những qủa bom từ trên trời rơi xuống hàng ngày, nhưng

phải cẩn thận tránh những qủa bom chưa nổ, đề phòng bệnh sốt rét, thương hàn cũng

như những con vắt ở trong rừng.

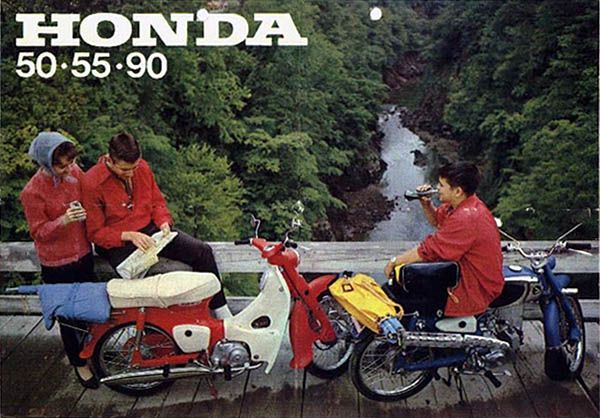

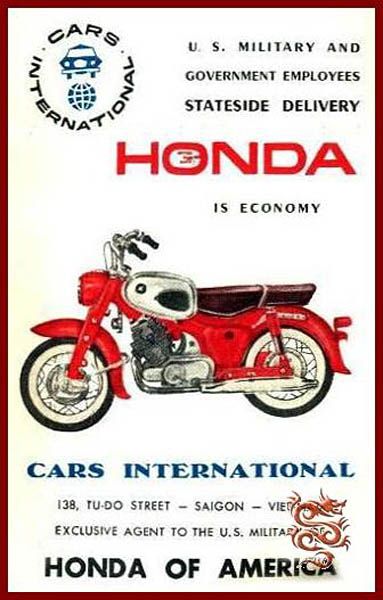

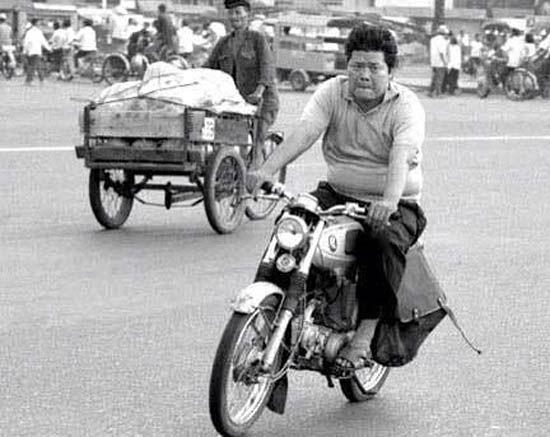

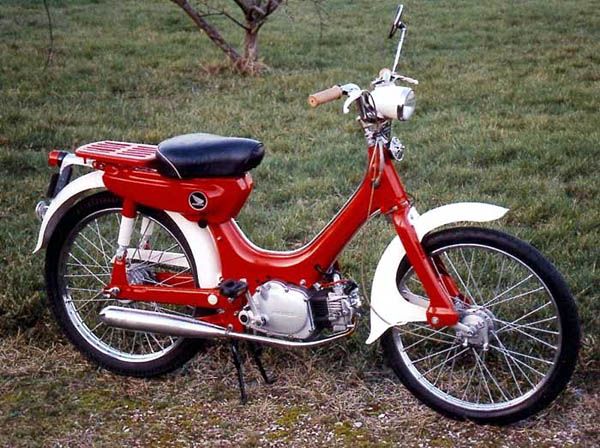

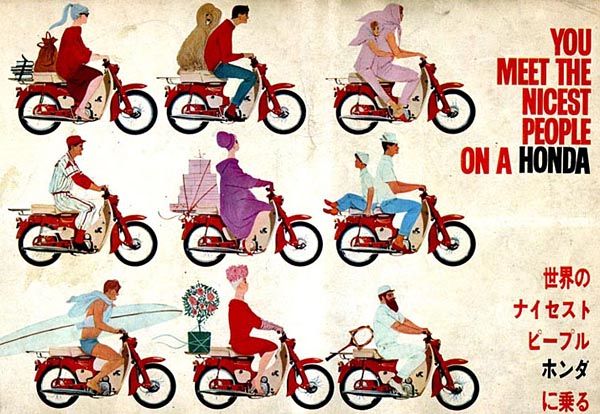

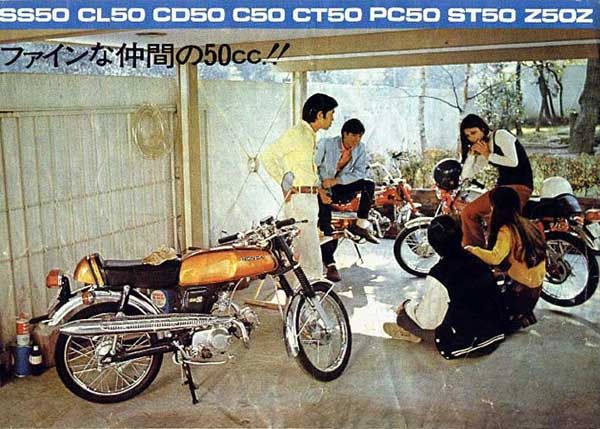

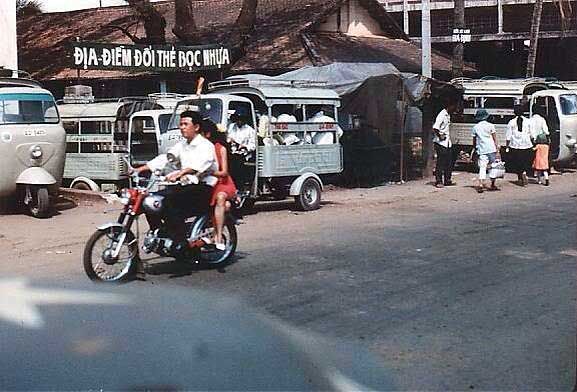

Lái chiếc xe Honda cũ đã 25 năm tên là con Báo Hồng,

từ Hà Nội thủ đô của nước Việt Nam đi về hướng nam, xuyên qua những khu vực hẻo

lánh miền Đông Nam Á châu. Đó là một chuyến đi ngoạn mục, chiến đấu với điạ hình,

điạ thế khó khăn, đôi khi xuống tinh thần, sợ hãi, có lúc vui khi gặp những vị

trưởng làng (tù trưởng sắc dân thiểu số), hoặc những người khai thác gỗ rừng bất

hợp pháp.

Đi một mình

Trong chương mở đầu tác phẩm, Antonia chia sẻ những điều

suy nghĩ và sự lo sợ về chuyến đi sắp đến khi cô chuẩn bị cho chuyến đi một mình

từ Hà Nội.

Tôi thức giấc khi những tia sáng bình minh chiếu qua

lớp rèm che cửa sổ khách sạn. Việt Nam dậy sớm và đường phố bên ngoài đã tấp nập

tiếng ồn ào xe cộ, tiếng người quét dọn. Khó có thể hình dung, trong vài giờ nữa,

tôi sẽ hòa mình vào làn sóng xe cộ, xuôi về hướng nam. Nhưng tôi đã làm, lái xe

uốn theo những khúc quanh co của con đường. Không quay trở lại.

Mặc dầu với những lo âu, nhưng tôi đã nhất quyết làm

một mình. Tôi đã đi nhiều nơi ở Ấn Độ trong những năm đầu lứa tuổi hai mươi, tất

cả những chuyến du hành đó đều đi chung với bạn. Năm 2006, người bạn thân Jo cùng

với tôi lái chiếc Tuk Tuk của Thái Lan, phá kỷ lục, 12, 561 dặm từ Bangkok đi

Brighton. Ngoại trừ một lần thay đổi ở Yekaterinburg vì tiếng ngáy ngủ của Jo,

chúng tôi chia nhiệm vụ lái xe, và những trách nhiệm khác, chia sẽ những chuyện

buồn vui. Rồi chuyến đi thăm Biển Đen (Black Sea) cùng với Marley, nơi mà tôi rơi

xuống vị trí phụ thuộc của phái nữ. Dù sao chúng tôi cũng đã đi qua sáu quốc

gia. Qua năm sau, trong một chuyến đi băng giá theo lộ trình xưa Ural lên vùng

bắc cực của nước Nga, tôi có thêm hai ông bạn can đảm, một người là diễn viên sân

khấu, người kia là chuyên viên cơ khí. Trong những chuyến du hành khác, tôi thường

có thêm chuyên viên thâu băng video (cho đài truyền hình), người thông ngôn, tài

xế, y tá, … Đi cả đoàn người ít nguy hiểm hơn.

Người bán bảo hiểm cho tôi đã áy náy nói rằng “Sẽ dễ

dàng hơn nếu tôi thay đổi chương trình, có thêm người bạn đồng hành”. Đi du hành

thám hiểm một mình bằng xe gắn máy (Honda) là cơn ác mộng cho công ty bán bảo

hiểm. Không phải chỉ riêng vấn đề tai nạn dễ xẩy ra hơn, lỡ gặp chuyện khó khăn

giữa đường thì tính sao? Có thêm người, vẫn có thể chạy đi tìm người cứu giúp.

Chỉ một thân một mình, lỡ bị sái chân, đau đầu, không có ai giúp đỡ.

Những chuyện rủi ro không làm tôi ngại, tôi muốn chứng

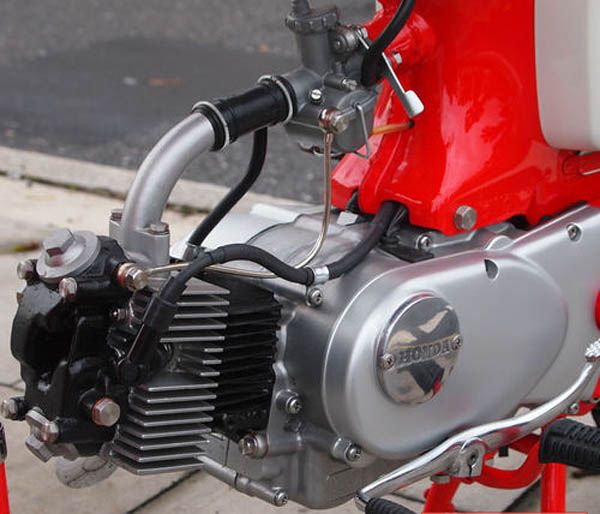

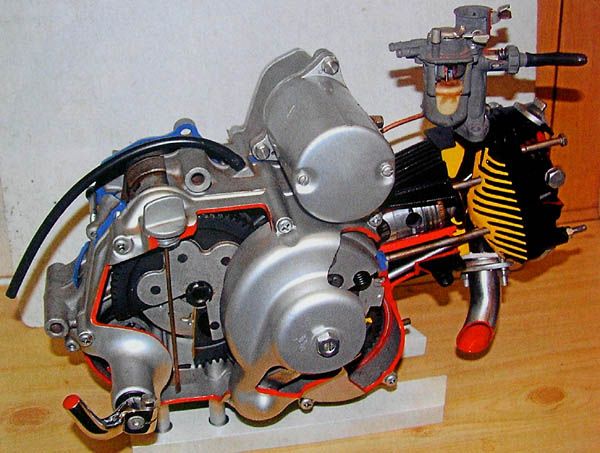

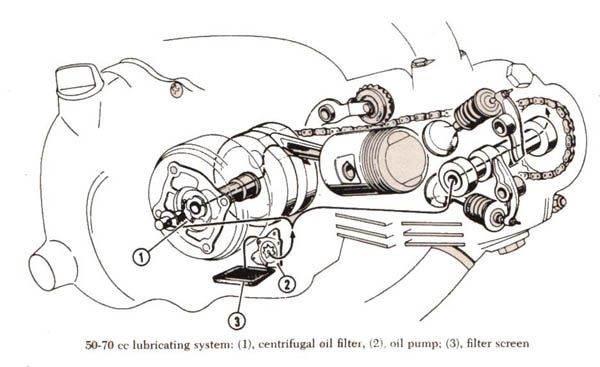

minh khả năng của mình bằng thể lực, bằng cảm xúc. Tôi có thể sửa được chiếc xe

gắn máy nếu bị ngưng lại giữa giòng suối cạn? Tôi ngủ trên một chiếc võng giữa

cánh rừng già được không? Tôi sẽ tính sao khi đến một làng Thượng hẻo lánh một

thân một mình? Trường hợp gặp đám cướp giữa đường?

Trước đó khoảng một tháng, tôi đang ngôi uống trà

trong một buổi phỏng vấn trên đài truyền hình ở Tanzania (Phi châu), bỗng liếc

thấy một con vật gì mầu đỏ vàng đang bò trên vai. Tôi hét to rồi nhẩy bật lên làm

cho tách trà rơi xuống đất. Sau đó vài giây, chuyên viên thâu hình cho biết, đó

là con “cánh cam” vô hại. Ông ta thốt lên “Chúa Jesus! Cô định đi Việt Nam

trong vài tuần sắp tới?”, rồi cười ha hả.

Một lần khác, trên đường đi Briston, Marley hỏi tôi,

“Cô tính sao về chuyện sửa xe gắn máy?” “Tôi sẽ mua cuốn Cẩm Nang xe Gắn Máy

cho người… lơ tơ mơ”. Anh ta trả lời “Tôi nghĩ có lẽ hơi ‘cao cấp’ cho cô”.

Đã có lần lái xe gắn máy, tôi không trông thấy một

xe hơi chạy ra từ một con đường nhỏ bên tay phải. Lần đó làm cho tôi hú hồn, nhói

tim. “Chúa ơi! Nghĩ đến chuyện lái xe gắn máy ở Việt Nam là một điều hãi hùng”

Tôi không thể sống một cách lặng lẽ, êm thấm như những

người đàn bà khác, lệ thuộc vào người đàn ông, ngay cả việc thay bóng đèn. Nếu

tôi lúc nào cũng đi cùng người khác, tôi sẽ không bao giờ phải đối đầu với sự yếu

ớt của chính mình. Sẽ có lúc chia sẻ với người bạn đồng hành như Marley, nhưng

có lúc phải thực hiện một mình.

Tôi ăn điểm tâm nhanh chóng, có quả banh nhỏ đang lăn

lộn trong bụng tôi về sự lo âu. Tôi dọn dẹp phòng khách sạn rồi chất đồ lên chiếc

xe gắn máy. Hành lý của tôi thật ít ỏi, gọn gàng, phải lấy xuống, chất lên hàng

ngày nên chỉ mang theo những vật dụng cần thiết. Đi du hành, đem theo đồ đạc

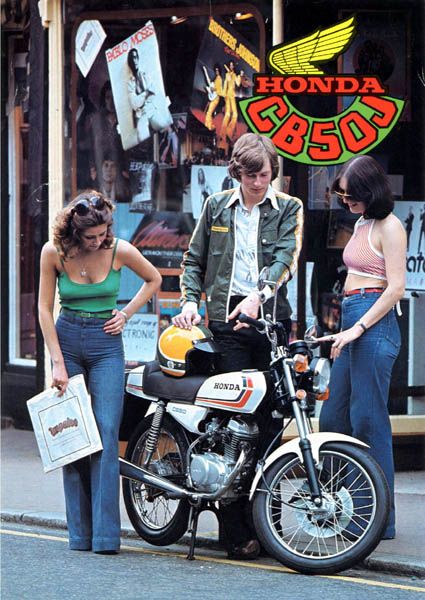

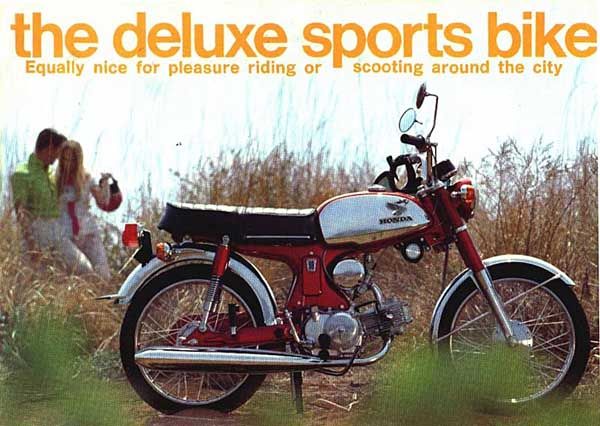

nhiều, lỉnh kỉnh là điều không nên. Chiếc xe gắn máy cũng vậy, rẻ tiền, đơn giản,

tôi không muốn đến một ngôi làng hẻo lánh trên một chiếc xe bóng láng, đắt tiền.

“Đồ nghề” của tôi gồm có hai túi treo hai bên nệm xe (yên xe), mua đấu giá trên

mạng eBay giá 20 pounds (Bảng Anh). Một thùng như thùng đựng bánh Pizza giao hàng

phiá sau và một hộp nhỏ đựng đồ đàn bà phía trước. Thùng nhỏ phiá trước chứa những

vật dụng quan trọng như máy vi tính (laptop), điạ bàn, bản đồ, máy chụp ảnh và

giấy tờ như bằng lái xe quốc tế, giấy tờ xe, passport và Visa. Thùng nhỏ này được

gắn lên xe ở Hà Nội vào phút chút do ông bạn tên Cường tặng. Một trong hai túi

trêo bên hông xe, chứa hai quần jean, áo dài tay, và những bộ quần áo thường khác.

Túi bên kia đựng đôi giầy, túi cứu thương, bong bóng (cho trẻ con), máy sạc điện

bằng năng lượng mặt trời, võng, nước uống.

Trang phục bên ngoài, sợi giây thắt lưng lớn có ngăn

dấu tiền, thẻ tín dụng. Trong túi quần có ít tiền điạ phương, điện thoại di động

và một máy định hướng (GPS) cầm tay, một quyển cẩm nang những câu thường dùng

tiếng điạ phương. Tôi còn dấu tiền ở bốn chỗ khác, trong thùng sau xe, trong

xe, đề phòng trường hợp khẩn cấp.

Tôi chào từ giã nhân viên khách sạn, đội nón bảo hiểm,

rồi lên đường.

vđh dịch thuật

'For the first time in my life I felt that death was a possibility; a

stupid, pointless, lonely death on the aptly named Mondulkiri Death

Highway.' The Ho Chi Minh Trail is one of the greatest feats of military

engineering in history. But since the end of the Vietnam War much of

this vast transport network has been reclaimed by jungle, while

remaining sections are littered with a deadly legacy of unexploded

bombs. For Antonia, a veteran of ridiculous adventures in unfeasible

vehicles, the chance to explore the Trail before it's lost forever was a

personal challenge she couldn't ignore - yet it would sometimes be a

terrifying journey. Setting out from Hanoi on an ageing Honda Cub, she

spent the next two months riding 2000 miles through the mountains and

jungles of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Battling inhospitable terrain and

multiple breakdowns, her experiences ranged from the touching to the

hilarious, meeting former American fighter pilots, tribal chiefs,

illegal loggers and bomb disposal experts. The story of her brave

journey is thrilling and poignant: a unique insight into a little known

face of Southeast Asia.

Biography

Antonia's - better known as Ants - favourite occupation is embarking on very long journeys in unsuitable vehicles; a habit which started in 2006 when she drove a bright pink tuk tuk from Bangkok to Brighton with her friend Jo. Through the trip the duo raised £50,000 for Mind, set the world record for the longest ever journey by auto-rickshaw, wrote a best-selling travel book Tuk tuk to the Road, and won Cosmopolitan magazine's Fun Fearless Female Award.Since then Ants has ridden a Honda C90 3000-miles around the Black Sea, organised the Mongol Derby, the longest horse race in the world, and survived an attempt to reach the Arctic Circle on an old Russian Ural and sidecar. Her articles have appeared in Wanderlust, The Guardian, Adventure Journal (USA), Verge (Canada) and Motorcycle Monthly, amongst others.

She's also appeared on numerous radio and TV shows, including Richard & Judy and Excess Baggage. In between travelling and writing she produces TV programmes for the BBC, Channel 4 and ITV.

Her next book, A Short Ride in the Jungle, will be published by Summersdale on April 7, 2014. The book recounts Ants' somewhat hair-raising solo motorbike mission down the remnants of the legendary Ho Chi Minh Trail in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Review

‘Compassionately but without sentimentality, Ants describes lands victimised in the recent past by militarism at its worst and now assaulted by consumerism at its most ruthless. She also provides many entertaining vignettes of eccentrics met en route, disasters narrowly avoided and happy encounters with kind people in remote regions of wondrous beauty.’(Dervla Murphy, legendary Irish travel writer)|‘Truly wonderful…a lovely book, very much after my own heart.’

(Ted Simon, author of Jupiter’s Travels.)|‘A beautifully written tale teeming with descriptive gems and wickedly funny anecdotes, all delivered in an earthy, self-effacing style that has the words spilling off the page. Utterly absorbing and impossible to put down. A traveller’s delight and classic-to-be!’

(Jason Lewis, author and the first person to circumnavigate the planet by human power alone)|‘Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent’s new book is a gripping travelogue which is at once both intimate and worldly-wise. Honest in her bravery (and brave in her honesty), she recounts a thrilling journey, not just through the splendour of South-East Asian landscapes, but also through the horror of Southeast Asian history – all atop the seat of the world’s most iconic motorbike.’

(Charlie Carroll, author of No Fixed Abode)|‘Ants has pulled off not only a demanding and original adventure but a great read too. A Short Ride in the Jungle informs and entertains in just the right measures, taking the reader on an action packed journey through Southeast Asia’s trails and jungles, as well its equally torrid history.’

(Lois Pryce, Motorcycle Adventurer and Author)|‘An epic book about an epic trail. Bolingbroke-Kent captures the sights, sounds and colour of the legendary Ho Chi Minh Trail in all its surviving glory. And she captures it the only realistic way – on the back on an ageing motorbike.’

Antonia is a travel writer,

ladyventurer, speaker, and lover of gin, motorcycles and tuk tuks.

After years of travelling as part of a television crew or with

companions, she decided she wanted to experience a true adventure on her

own, in her own words, "The sort where I would find myself lost in the

middle of the Southeast Asian jungle with nothing to survive but twigs

and peanut butter".

Complete with a beautiful

Pink(ish) Panther motorcycle, Antonia started her journey across the Ho

Chi Minh Trail in the spring of 2013. We’re sharing with you an extract

of her novel A Short Ride in the Jungle: The Ho Chi Minh Trail by Motorcycle with details of where to purchase below.An introduction to her journey

Constructed between 1959 and 1975, the Ho Chi Minh Trail once spread 12,000 miles through the mountains and jungles of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Arguably one of the greatest feats of military engineering in history, the Trail was a paragon of ingenuity and bloody determination, the means by which the North Vietnamese fed and fought the war against the US-backed South. Without it there could have been no war, a fact which the Americans knew only too well: in a sustained eight year campaign to destroy it they flew 580,000 bombing missions and dropped over 2 million tonnes of ordinance on neutral Laos, denuded the jungle with chemicals and seeded clouds to induce rain and floods. At one point Nixon even mooted the notion of deploying nuclear weapons.While scores of travellers ride a tourist-friendly, tarmac version of the Trail between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, only a handful follow its gnarly guts over the Truong Son Mountains into Laos. Even fewer trace it south into the wild eastern reaches of Cambodia. Antonia wanted to do both. Unlike the hundreds of thousands of North Vietnamese who walked, drove and worked on the Trail in the sixties and seventies, she wouldn’t have to deal with a daily deluge of bombs. But UXO, unexploded ordnance, littered her route south, cerebral malaria, dengue fever and dysentery were still prevalent and the trees slithered and crawled with unpleasant creatures.

Riding a 25-year old Honda Cub known as the Pink Panther, Antonia rode south from Hanoi, the cacophonous capital of Vietnam, through some of the remotest regions of Southeast Asia. Battling inhospitable terrain and multiple breakdowns, it was a journey that ranged from the hilarious to the mildly terrifying, during which she encountered tribal chiefs, illegal loggers, former American fighter pilots, young women whose children had been killed by UXO, eccentric Ozzie bomb disposal experts and multiple mechanics…

Going Solo

In the beginning of her novel, Antonia shares her thoughts and fears about the journey ahead as she prepares to embark alone from Hanoi.

I awoke as the first glimmer of dawn broke through the hotel curtains. Vietnam rises early and already the street outside was humming with the noise of mopeds and the clatter of opening shutters. It was almost too much to comprehend that in a few hours I’d be zipping up my panniers, turning into the traffic and heading south. But here I was, the swirling depths of the unknown beckoning me forward. There was no going back now.Despite my fears about the journey, I’d been determined to do it alone. Bar a stint backpacking around India in my early twenties, all my travels had been with other people. In 2006 my dear friend Jo and I drove a bright pink Thai tuk tuk a record- breaking 12,561 miles from Bangkok to Brighton. Aside from an altercation in Yekaterinburg over Jo’s snoring we got on brilliantly, splitting the driving and responsibilities, making each other laugh and mopping up the odd tears. Then there was my Black Sea trip with Marley, where I’d too easily fallen into the dependent female role, never so much as picking up a spanner as we trundled through six countries. The following year, in a shivering attempt to cajole an old Ural to the Russian Arctic Circle, I’d been with two fearless male friends, one a tap-dancing comedian, the other a consummate mechanic. On every other expedition I had organised, or television programme I had worked on, there had been translators, drivers, medics and crew. It doesn’t mean that each and every mission wasn’t difficult in some way, but having other people around greatly mitigated the risk and adversity.

As my insurance company had nervously pointed out, it would be ‘a lot easier if you modified your plans and went with a travel companion.’ Travelling alone on a motorbike was a travel insurance nightmare. Not only had I opted for a vehicle with a high accident rate, but what would happen if I had a serious mishap miles from anywhere? If I was with another person, at least they would be able to ride or call for help. But alone, with a broken leg, bashed head or worse, there would be no one.

But the dangers weren’t enough to put me off. Company makes us idle, gives us masks to hide behind, allows us to avoid our weaknesses and cushion our fears. By peeling away these protective layers I wanted to see how I would cope, find out what I was really made of, physically and emotionally. Would I be able to fix my bike if it ground to a halt in the middle of a river? How would I handle nights spent in a hammock in the depths of the jungle? What would it feel like to ride into a remote tribal village alone? How would I react in times of real adversity? And could I outstrip Usain Bolt if confronted by a many-banded krait?

A month before, I’d been relaxing with a cup of tea during a television shoot in Tanzania when I spied something red and black crawling across my shoulder. I screamed and leapt a foot in the air, sending tea and filming equipment flying into the dust. After several hysterical seconds on my part, the camera assistant confirmed it was no more than a harmless beetle.

“Jesus – and you’re going to Vietnam in a few weeks?” he laughed.

And on another occasion, driving into Bristol not long before I left, Marley had asked me what I was going to do about fixing the bike. “I’ll get a book called The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Motorcycles.”

“I think that might be a bit advanced for you,” he jibed.

At that point I’d driven across a roundabout and failed to see a car coming out of a small road to the right. There was a sharp intake of breath from my left. “God, the thought of you driving a motorbike in Vietnam is terrifying.”

I couldn’t go through life acting like a character from The Only Way is Essex every time I encountered something with more than four legs. Nor did I want to turn into one of those women who relies on their other half so much they end up unable to change a light bulb. If I always travelled with other people, I would never have to confront my weaknesses. There would be times when I’d want to share a laugh or a moment with Marley or have a stiff gin with friends. But hopefully there would also be moments of simple achievement. It was times like these that going solo were all about.

I breakfasted in a daze, my back still knotted, a ball of anxiety lurking in the pit of my stomach. For the first of many times, I packed up my hotel room and loaded the bike. I’d wanted to keep my luggage as simple and light as possible. I would be loading and unloading the bike every day, so it would be foolish to travel with any more than the bare minimum. Plus, in the same way that I’d wanted a simple bike, I didn’t want to be riding through poor villages clanking with showy, expensive equipment. My kit consisted of two small textile panniers – bought on eBay for £20 – which slung over the seat behind me cowboy-style, a pizza delivery-style top box and a ladylike wire front basket. The top box carried essentials such as my laptop, compact toolkit, camera and paperwork: International Driving Permit, driving licence, bike registration papers, photocopies of passport and visas. The front basket – added in Hanoi at the last minute – held bike spares Cuong had given me, plus my daily water supply. One side pannier fitted my limited wardrobe: a fleece, a single pair of jeans and one long skirt, a handful of tops, a floral shirt, a sarong, waterproof trousers, a bikini, three pairs of knickers, two pairs of socks, one decent set of matching underwear and flip flops. Shoe-horned into the other side pannier, along with a basic medical kit, balloons to give to children, solar charger and jungle hammock, was a precious bottle of Boxer Gin. Embarking on a solo expedition into the jungle was unquestionable without an emergency supply of the juniper nectar.

Round my waist I strapped a concealed money belt containing a debit card and a small supply of cash. And over my top I wore a nerdy but incredibly useful bumbag with: an iPhone, a small amount of dollars and local currency, a handheld GPS unit, a local phrasebook and my coterie of lucky talismans. Other stashes of currency were hidden in my backpack and in a secret sealed compartment on the bike. Designed to hold a few tools, it was the perfect size for a small waterproof bag containing a spare credit card and an emergency supply of dollars. With money hidden in four different places, I’d be unlucky to be cleaned out entirely.

Without much ado I said goodbye to the hotel staff, pulled on my Weise helmet, jacket and gloves and set sail. No big rush of nerves, no big fanfare, just a quiet “Right, let’s go!” to the bike, a slight wobble, and off we were.

I was thankful I hadn’t asked anyone to come and see me off. I didn’t need the added pressure of people or photographs this morning. Digby had come to bid me goodbye the night before.

“Don’t forget to go to lots of cắt tóc”, he advised, pointing to the hairdresser next to the hotel where a woman was having her head massaged. ‘They’re fabulous; you can get your hair washed all the way down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. You don’t even need to take shampoo with you.’

Given the dangers and challenges I’d be facing on the road, hair washes and head massages weren’t something I had envisioned.

“Is that your parting advice?” I asked, probing for something more applicable.

“Yes. It’s about the little things in life. Now goodbye and good luck.”

Then I’d watched him turn right and vanish into the darkness, the last familiar face I would see before my journey began.

A Short Ride in the Jungle: the Ho Chi Minh Trail by Motorcycle

Having returned from the mud and jungles of Southeast Asia I sat down in in front of my laptop and set about the equally hard task of penning a book about my adventure. Six months, 100,000 words, five hundred cups of Earl Grey and four hundred dog walks later, I handed in my tome to my publishers, Summersdale. Now, a year after I was forcing the Pink Panther through that dastardly orange Trail mud, my book, A Short Ride in the Jungle, is now out.

*** TO BUY A SIGNED COPY DIRECT FROM THE AUTHOR, PLEASE CONTACT ME HERE!***

Here’s what a few people have said about it…..‘Compassionately but without sentimentality, Ants describes lands victimised in the recent past by militarism at its worst and now assaulted by consumerism at its most ruthless. She also provides many entertaining vignettes of eccentrics met en route, disasters narrowly avoided and happy encounters with kind people in remote regions of wondrous beauty.’ Dervla Murphy, legendary Irish travel writer

‘Truly wonderful…a lovely book, very much after my own heart.’ Ted Simon, author of legendary motorcycling tome Jupiter’s Travels.

‘A beautifully written tale teeming with

descriptive gems and wickedly funny anecdotes, all delivered in an

earthy, self-effacing style that has the words spilling off the page.

Utterly absorbing and impossible to put down. A traveller’s delight and

classic-to-be!’

Jason Lewis, author and the first person to circumnavigate the planet by human power alone

‘A jaw-dropping adventure, part travelogue, part thriller….an adrenaline-fuelled, fascinating ride.’ Cosmopolitan magazine.

‘Fantastic.’ Overland Magazine.

‘Exceptionally well researched…personal,

emotional…perfectly written, demonstrating just how travel by motorbike

can be used to inform, educate and entertain the reader… a great book.’

Adventure Bike Rider magazine.

‘Thrilling and poignant: a unique insight into Southeast Asia.’ The Bristol Magazine.

‘Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent’s new book is a

gripping travelogue which is at once both intimate and worldly-wise.

Honest in her bravery (and brave in her honesty), she recounts a

thrilling journey, not just through the splendour of South-East Asian

landscapes, but also through the horror of Southeast Asian history – all

atop the seat of the world’s most iconic motorbike.’ Charlie Carroll, author of No Fixed Abode

‘Ants has pulled off not only a demanding and original adventure but a great read too. A Short Ride in the Jungle informs and entertains in just the right measures, taking the reader on an action packed journey through Southeast Asia’s trails and jungles, as well its equally torrid history.’ Lois Pryce, Motorcycle Adventurer and Author

‘An epic book about an epic trail.

Bolingbroke-Kent captures the sights, sounds and colour of the legendary

Ho Chi Minh Trail in all its surviving glory. And she captures it the

only realistic way – on the back on an ageing motorbike.’ Kit Gillet, Freelance Journalist and Videographer

To see more reviews on Amazon from people who have bought the book please click here. As of July 2014 it has solid 5 star reviews.

The book was released in April 2014 and

is available in all major UK bookshops, as well as on Kindle. It is

also available at selected outlets worldwide; here are a few…

Monument Books, Phnom Penh; Kinokunya

stores, Malaysia, WH Smith Airport stores, Malaysia; Asia Books,

Thailand; the Bookwork, Hanoi… as well as other stores throughout Asia

and in Africa, Australia and NZ. It will be available in the US and

Canada sometime in 2015.